Obvious Leo wrote: The Buddha taught that all fixed forms, like objects, people or ideas, are nothing but "maya".... In our ignorance (avidya) we perceive our world as fixed and permanent but this is not truth. Our world is definable only in terms of its changes and the Self more so than anything else. On the path to enlightenment which the Buddha taught, the key step was to rid ourselves of this notion of a separate and permanent Self and replace it with a Self ever-changing and transient. The separate and unchanging self leads to pain and suffering (duhkha), so Buddha and Descartes would have found little to chat about. Buddha would also have described the "hard problem" as an obvious example of seeking maya.

The Buddhist term is not 'maya' - which is from the Hindu Vedanta - but 'samsara', which means 'subject to continual birth and death' (although the two concepts are obviously similar.) According to Buddhism, beings are involuntarily trapped in the samsara of birth and death, to all intents forever, unless they are fortunate enough to encounter the Buddha's teaching and understand how to liberate themselves.

It is true that Buddhism is not 'substantialist', i.e. teaches that there is nothing fixed, permanent or eternal. However this is a very subtle idea and prone to misinterpretation - there are endless debates on Dharma forums about it.

According to Buddhism, were many different errors of this kind, which fell under two main headings: nihilism and 'eternalism'. Nihilism is fairly straightforward: it is simply the view that the human is the physical body and that on death, there is no rebirth or any further karma. (It is the view of probably the majority of the non-religious and certainly of all materialists

1.) The 'eternalist' error is much harder to understand, but it is the idea that the self or soul is a permanently existing entity that will migrate from life to life forever. Recall that these debates were conducted in a culture where the notion of transmigration had been established for millenia already; the scriptural discussions of these ideas are often preceeded by the phrase about a 'recluse or brahmin who recalls one, or many, or thousands of previous lives'.

So the 'middle path' of Buddhism avoids both these extremes of 'nihilism and eternalism'. However in my experience, it is extremely easy for Buddhism to be interpreted (or mis-interpreted) nihilisticaly, i.e. 'there is no self and nothing permanent' is taken formulaically and not really understood (even by many with life-long commitment to the Buddhist path. It is a fact that the Hindu opponents of the Buddha, and indeed many of the European scholars who first translated Buddhist texts, saw Buddhism as an essentially nihilist philosophy.)

In any case, my interpretation is that 'insight into impermanence' is really a matter of what Aristotle would call 'practical wisdom'. In effect it means that everything you (or 'the world') treasures, like possessions, appointments, status, relationships, and so on, are empty and ultimately insubstantial. We must learn to be happy, depending on nothing.

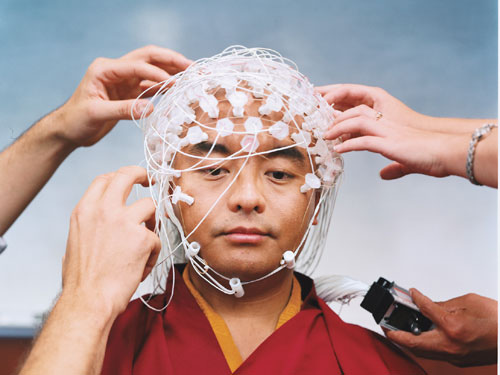

As regards the remark on the Buddha and Descartes, in fact Tibetan philosophy of mind often appears quite Cartesian, in effect. The following is an excerpt from the Dalai Lama on the topic of reincarnation where he argues that there is a clear

ontological distinction between mind and matter. This is given in the context of discussing the basis for reincarnation:

There are many different logical arguments given in the words of the Buddha and subsequent commentaries to prove the existence of past and future lives. In brief, they come down to four points: the logic that things are preceded by things of a similar type, the logic that things are preceded by a substantial cause, the logic that the mind has gained familiarity with things in the past, and the logic of having gained experience of things in the past.

Ultimately all these arguments are based on the idea that the nature of the mind, its clarity and awareness, must have clarity and awareness as its substantial cause. It cannot have any other entity such as an inanimate object as its substantial cause. This is self-evident. Through logical analysis we infer that a new stream of clarity and awareness cannot come about without causes or from unrelated causes. While we observe that mind cannot be produced in a laboratory, we also infer that nothing can eliminate the continuity of subtle clarity and awareness.

As far as I know, no modern psychologist, physicist, or neuroscientist has been able to observe or predict the production of mind either from matter or without cause. 2.

This is an extension of the idea that 'nothing happens without a cause', but goes further in saying that 'like effects require like causes', i.e. mind does not arise from material causation; mind is a continuum, or, in the traditional sense, 'a substance', that is, something that is not dependent on or reducible to other things.

--------------------------------------------------------

1. The view that humans life is the result of 'fortuitous causes' is also rejected by the Buddha, a view that translator Bikkhu Bodhi notes 'has become the dominant outlook of the present-day materialist, which he takes to be the dictum conclusively proven by modern science'. In the Buddhist view, the dominant (but not only) factor determining human existence is karma.